Functional programming sparks joy 2

Last updated: 20 September 2019

Previous card: Functional programming sparks joy

Before adding more concepts, I would like to share a reflection.

I think that object-oriented programming and functional programming are such different paradigms that they are not comparable. However, I find a similar feeling.

When I discovered object-oriented design patterns, I realized that we weren’t doing anything special. Our problems were widespread.

The only difference between our development project and others could be the business domain.

What if we step forward? What if we can model the domain with two kinds of pieces?

When I was a child, I didn’t have LEGO bricks but TENTE with smaller pieces.

I still remember my helicopter of the forest brigade:

I assembled it and disassembled it hundreds of times.

However, it had more than two kinds of pieces.

What if we only need two kinds of pieces for creating software?

What if there is a branch of mathematics that tries to generalize things with two kinds of pieces and can be moved to computer programming?

I’m talking about category theory where a category is a collection of:

- Objects

- Relationships (also known as morphisms or arrows) between the objects

Functional programming is based on a category of sets where:

- The objects are types (sets of values)

- The arrows are functions

Just two kinds of pieces and the power of composition with all the abstractions defined and proved matematically.

As Bartosz Milewski wrote:

One of the important advantages of having a mathematical model for programming is that it’s possible to perform formal proofs of correctness of software.

- From objects of a category to objects of another one

- From arrows of a category to arrows of another one

Therefore, in functional programming:

- The objects are types and functions

Remember that functions are first-class citizens and can be input and output as well.

It’s awesome the amount of things that can be built when “playing” with only two kinds of pieces.

Bartosz Milewski also wrote:

Category theory is full of simple but powerful ideas

Let’s review the other previous concepts (I already mentioned functions as first-class citizens):

- If functions were impure, it would be very difficult to “play” with them and to compose with each other.

- Mathematically, the common needs with types and functions are defined. We only have to use them, so we’ll program in a higher abstraction level.

- Immutability is also essential to compose functions. Otherwise, the results couldn’t be anticipated.

- Recursion will appear when defining types or functions.

- Currying and partial application are some of the techniques to be able to compose functions (an output must match with the input of the following function).

Finally, let’s consider the business domain we are working on, the state machines, the processes, the transformations, the validations, … how do types and functions fit those needs? It seems they absolutely fit them.

About the examples

So far, I’ve used plain JavaScript and an example with Lodash library.

However, to continue explaining functional programming, I’ll include examples in PureScript, a strongly-typed functional programming language that compiles to JavaScript. It’s heavily influenced by Haskell.

I would have had a clear choice with other non-purely programming languages:

I think it’s good to have libraries which add functional capabilities as a way of extending a language more quickly and with the support of the developers community.

However, I had a lot of alternatives in JavaScript:

- Libraries: Lodash, Underscore, Rambda, etc.

- Languages which compile to JavaScript: TypeScript, PureScript, Elm, ClojureScript, Reason, OCaml (the last two options thanks to BuckleScript), etc.

Why PureScript? I made the decision when trying to explain composite types:

- Libraries such as Lodash or Underscore don’t allow to create sum types.

- Ramda library provides Either, though it’s for doing an OR of function results.

- I found a library for creating sum types: Daggy. However, this alternative involved making more decisions later.

- TypeScript uses the pipe to represent the choice between basic types or the intersection of properties between objects.

- I found composite types in Reason, though I didn’t find other capabilities.

- What about the rest of options? I reviewed PureScript and it provided the characteristics I was looking for.

My only purpose is explaining functional programming. PureScript is only a choice for it.

Declaration and definition

In PureScript, as in Haskell, it’s a good practice to provide type annotations as documentation though compiler is able to infer them.

The function type annotation is known as the function declaration. Its notation is influenced by Hindley-Milner type system and it has the following parts:

- Function name

::(= “is of type” or “has the type of”)- Function type:

- Input type

->- Output type

The function definition is where the function is actually defined.

For instance, the declaration and definition of add function:

add :: Int -> Int -> Int

add x y = x + y

add function is really:

add :: Int -> (Int -> Int)

It takes an integer (the first operand) and returns a function. That function takes the other integer (the second operand) and returns the sum.

This is transparent to us because the function definition and the use work like a function of 2 parameters.

Composite types

Types can be combined to create a new type.

The new type is also known as an algebraic data type (ADT).

Why algebraic? Because we can “play” with them on equations and symbols (I didn’t cover it here although it’s fun!).

There are two common kinds of composite types:

- Product types

- Sum types

Let’s see what they are and some examples and then I’ll explain a curiosity that can be useful to understand the reason of their names.

Product types

This is an example of the creation of a new type with the product of two types:

data Money = Money {

amount :: Amount,

currency :: Currency

}

Its values will contain both a value of type Amount and a value of type Currency.

Why product? Think about the number of different values for that type: the product of the number of different values of the type Amount and the number of different values of the type Currency.

Sum types

This is an example of the creation of a new type with the sum of two types:

data SendingMethod

= Email String

| Address { street :: String,

city :: String,

country :: String }

The new type SendingMethod represents a choice between Email and Address.

The values of this new type will contain a value of type Email or a value of type Address.

Why sum? Think about the number of different values for that type: the sum of the number of different values of the type Email and the number of different values of the type Address.

Pattern matching

In functional programming, pattern matching is based on constructors as patterns.

Given a value, it can be disassembled down to parts that were used to construct it.

This is a powerful tool to make decisions according to types:

showSendingMethod :: SendingMethod -> String

showSendingMethod sendingMethod =

case sendingMethod of

Email email -> "Sent by mail to: " <> email

Address address -> "Sent to an address"

Some composite types

Tuple

Tuple is an example of product type that represents a pair of values.

It’s defined in the module Data.Tuple of PureScript:

data Tuple a b = Tuple a b

where:

- The lowercase letters

aandbrepresent any type - The first

Tupleis the type constructor - The second

Tupleis the value constructor

Let’s see an example:

pair :: Tuple String String

pair = Tuple "spam" "eggs"

where:

- The type constructor

Tupleis used in the declaration:pairis of typeTuple String String - The value constructor

Tupleis used in the definition: the value ofpairisTuple "spam" "eggs"

It’s known as Pair in other languages.

Maybe

Maybe is an example of sum type that is used to define optional values.

It’s defined in the module Data.Maybe of PureScript:

data Maybe a = Nothing | Just a

where:

- The lowercase letter

arepresents any type Maybeis the type constructor

Maybe of a type can represent one of these options:

- A missing value:

Nothing - The presence of a value of that type:

Just a

Let’s see an example of use:

showTheValue :: Maybe Number -> String

showTheValue value =

case value of

Nothing -> "There is no value"

Just value' -> "The value is: " <> toString value'

It’s known as Option in other languages.

Either

Either is another example of sum type and it’s commonly use for error handling.

It’s defined in the module Data.Either of PureScript:

data Either a b = Left a | Right b

where:

- The lowercase letters

aandbrepresent any type Eitheris the type constructor

Either represents the choice between 2 types of values where:

Leftis used to carry an error valueRightis used to carry a success value

Let’s see an example of use:

showTheValue :: Either String Number -> String

showTheValue value =

case value of

Left value' -> "Error: " <> value'

Right value' -> "The value is: " <> toString value'

Some guidelines

Making things explicit

It can be said that functional programming is based on making things explicit as much as possible.

For instance, let’s think about Maybe.

If a function returns an integer, a missing value is not expected.

With Maybe, it can be made explicit that the function returns an integer or not.

Making illegal states unrepresentable

This is a design guideline by Yaron Minsky.

Let’s see an example. Imagine that we have a type Course with this content:

data Course = Course {

title :: String,

started :: Boolean,

lastInteraction :: Maybe Date

}

There is an illegal state that can be representable: started is false and lastInteraction has a date.

For instance, that illegal state could be avoided with a sum type:

data Course

= StartedCourse { title :: String, lastInteraction :: Date }

| UnstartedCourse { title :: String }

Make interfaces easy to use correctly and hard to use incorrectly.

Interfaces occur at the highest level of abstraction (user interfaces), at the lowest (function interfaces), and at levels in between (class interfaces, library interfaces, etc.)

Typeclasses

A typeclass defines a family of types that support a common interface

Typeclasses are useful to define concepts like monoids, functors, applicative and monads for all the types or types constructors, respectively.

And then, it’s possible to create instances of those typeclasses for concrete types or types constructors.

I include more details about it in following sections.

Monoids

A monoid is useful to explain how the values of a type are combined.

Let’s see some examples with known types.

For instance, natural numbers:

- They could be combined with addition, for instance.

- Zero could be the starting point and then, add each number.

- Given 3 numbers, the result with be the same for these operations:

- The addition of the first 2 numbers is added with the third number.

- The first number is added with the addition of the other 2 numbers.

Or strings:

- They could be combined with concatenation.

- An empty string could be the starting point and then, concatenate each string.

- Given 3 strings, the result with be the same for these operations:

- The concatenation of the first 2 strings is concatenated with the third string.

- The first string is concatenated with the concatenation of the other 2 strings.

How to express it in an easy way?

Monoids to the rescue!

Read the following definition together with the previous examples.

A monoid is a type with a binary operation (2 elements). That operation has the following properties:

- It has a neutral element (identity)

- It’s associative

Did you identify each part of the definition in the previous examples?

Typeclass for monoids

Let’s see how to abstract the concept of monoid for any type and then, how to define it for concrete types.

In Haskell, the typeclass for a monoid includes the neutral element (called mempty) and the binary operation (called mappend):

class Monoid m where

mempty :: m

mappend :: m -> m -> m

However, PureScript has a previous abstraction and includes the binary operation in Semigroup typeclass:

class Semigroup a where

append :: a -> a -> a

So Monoid typeclass extends the Semigroup typeclass with the neutral element:

class Semigroup m <= Monoid m where

mempty :: m

That’s the abstraction. Now, for instance, how to define the way of combining strings?

The monoid for strings in PureScript (modules Data.Semigroup and Data.Monoid, respectively):

instance semigroupString :: Semigroup String where

append = concatString

instance monoidString :: Monoid String where

mempty = ""

The binary operation is concatenation and the neutral element is the empty string.

In this way, it’s possible to combine all the strings from an array into a single string when using the append and mempty defined for strings:

greeting :: String

greeting = foldl append mempty ["Hello,", " ", "world!"]

-- "Hello, world!"

foldl folds the array from the left. In this case, the result would be the same with foldr.

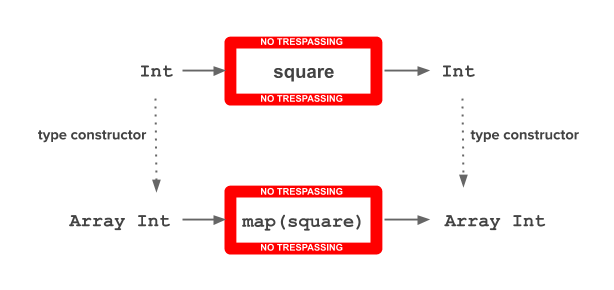

Functors

You already know a functor!!

A functor is a type constructor which provides a mapping operation.

Which functor do you know for sure?

Array is a functor which provides the map function.

Let’s remember the included example in the first part (plain JavaScript):

const square = number => Math.pow(number, 2);

const numbers = [2, 5, 8];

numbers.map(square); // [4, 25, 64]

The same example in PureScript:

square :: Int -> Int

square number = pow number 2

numbers = [2, 5, 8] :: Array Int

logShow (map square numbers)

-- [4,25,64]

or using an infix function application (as an operator between the two arguments):

logShow (square `map` numbers)

-- [4,25,64]

logShow (square <$> numbers)

-- [4,25,64]

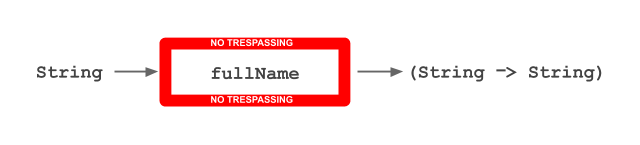

Graphically:

It’s said that:

- The

mapfunction allows the functionsquareto be lifted over an array - Or just, the

mapfunction lifts thesquarefunction

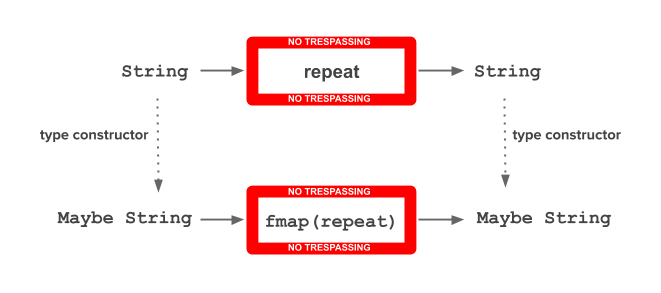

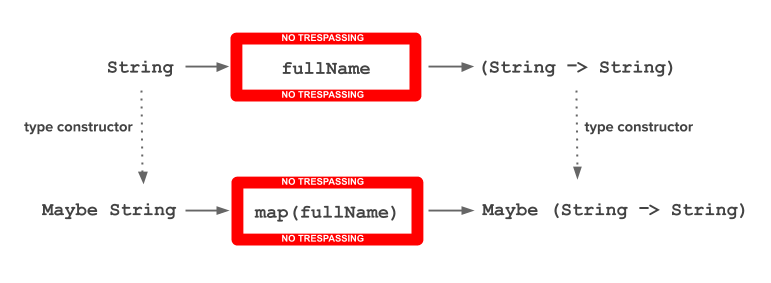

How to form a functor

Following the definition, a functor can be formed by:

- A type constructor

- A mapping function

For instance, the functor formed by:

- The type constructor

Maybe(in this case, fromStringtoMaybe String) - The following

fmapfunction:- From a function

(String -> String) - To a function

(Maybe String -> Maybe String)

- From a function

repeat :: String -> String

repeat aString = aString <> aString

fmap :: (String -> String) -> Maybe String -> Maybe String

fmap f value =

case value of

Nothing -> Nothing

Just value' -> Just (f value')

message :: Maybe String

message = fmap repeat (Just " bla ")

-- (Just " bla bla ")

Graphically:

In this example, the fmap function lifts the repeat function.

square and repeat which have the same type for input and output. However, that condition is not necessary.

Typeclass for functors

Let’s see how to abstract the concept of functor for any type constructor and then, how to define it for a concrete type constructor.

The typeclass for a functor appears in Data.Functor module:

class Functor f where

map :: forall a b. (a -> b) -> f a -> f b

Following the previous example, the functor for Maybe is already defined in Data.Maybe module:

instance functorMaybe :: Functor Maybe where

map fn (Just x) = Just (fn x)

map _ _ = Nothing

So it can be used to get the same result than before with less code:

repeat :: String -> String

repeat aString = aString <> aString

logShow (map repeat (Just " bla "))

-- (Just " bla bla ")

or using an infix function application (as an operator between the two arguments):

logShow (repeat `map` (Just " bla "))

-- (Just " bla bla ")

logShow (repeat <$> (Just " bla "))

-- (Just " bla bla ")

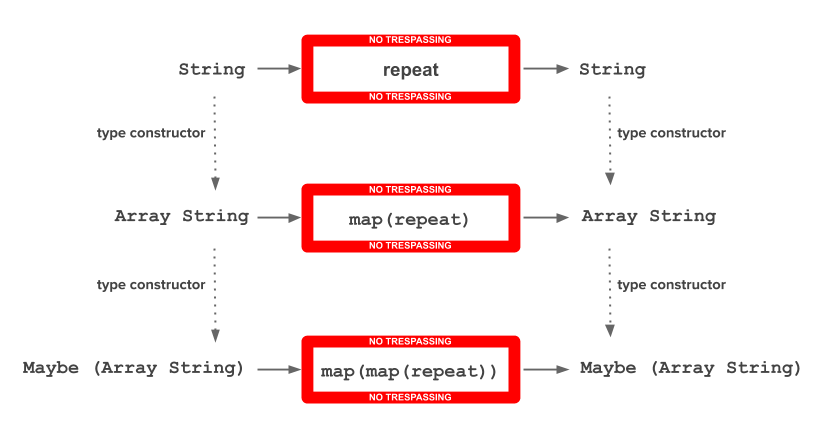

Functor composition

So far I’ve included examples of Array functor and Maybe functor separately.

What if there are more than one functor?

What if we want to apply the repeat function into a Maybe (Array String)?

Firstly, we use the mapping function of Array and then, the mapping function of Maybe over the result.

In other words, the mapping functions are composed (operator >>>):

logShow ((map >>> map) repeat (Just [" bla ", " ha "]))

-- (Just [" bla bla "," ha ha "])

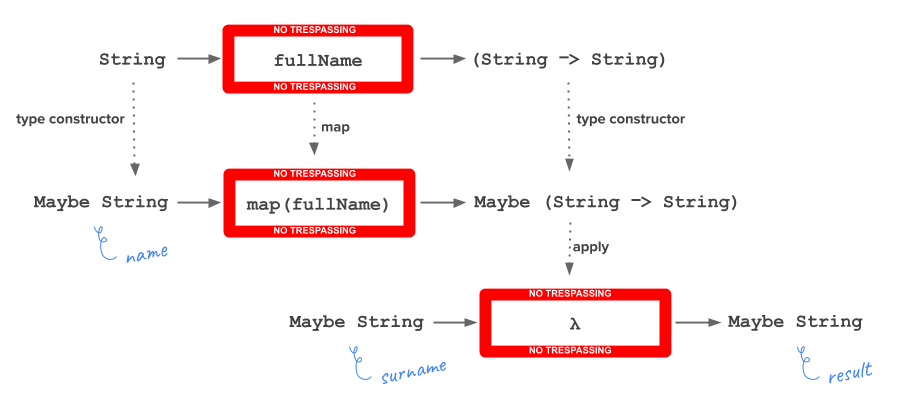

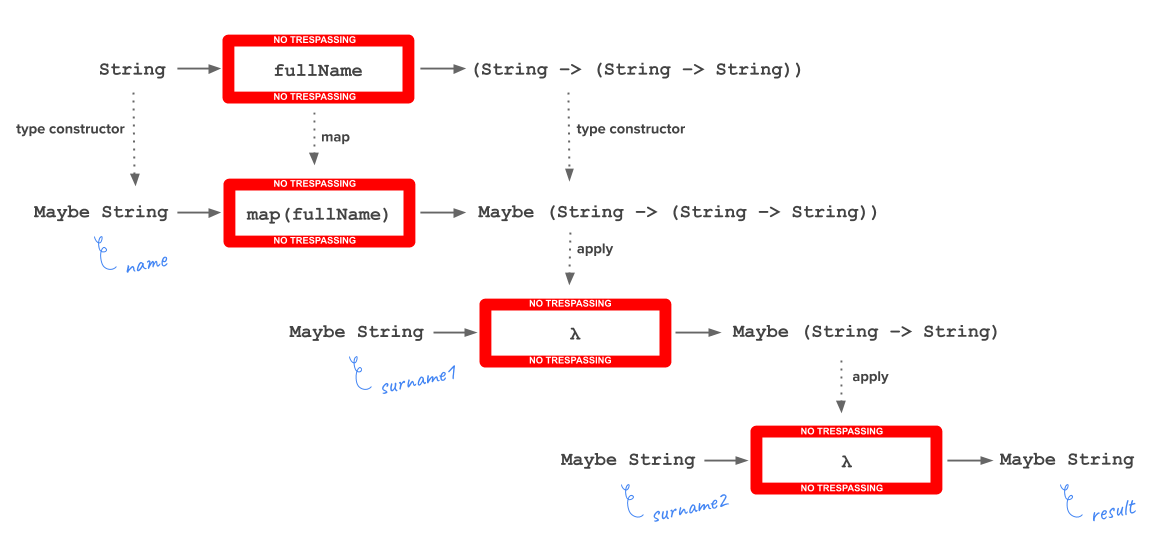

Applicative

There are a lot of things about applicative. I include the basic applicative abstraction also known as an applicative functor.

An applicative functor is an step further than a functor.

Let’s see what happens if we have a function with more than one parameter.

For instance:

fullName :: String -> String -> String

fullName name surname = name <> " " <> surname

Functions are curried by default in PureScript, so in this case: the input is a String and the output is another function String -> String.

What happens if instead of two strings for name and surname we have Maybe String for each of them?

With map from functorMaybe, we get another function from Maybe String to Maybe (String -> String).

In other words, the function String -> String is wrapped with the type constructor Maybe.

How can we continue?

How can we get another function from Maybe String to Maybe String?

apply to the rescue!

In PureScript, the applicative for Maybe is already defined so it’s possible to use apply with that kind of type constructor:

logShow (apply (map fullName (Just "Rachel")) (Just "M. Carmena"))

-- (Just "Rachel M. Carmena")

logShow (apply (map fullName (Just "Rachel")) Nothing)

-- Nothing

or using an infix function application (in this case, <*> is the equivalent to apply):

logShow (fullName <$> Just "Rachel" <*> Just "M. Carmena")

-- (Just "Rachel M. Carmena")

logShow (fullName <$> Just "Rachel" <*> Nothing)

-- Nothing

Therefore, if we have a function with more than two parameters, we’d use <$> (map) for the first parameter and then <*> (apply) for the rest of parameters.

Another powerful tool to compose functions. Think about other type constructors like Either, form validations, etc.

Finally, after the examples, it could be easier to understand the difference between map from functors and apply from applicative functors:

map :: forall a b. (a -> b) -> f a -> f b

apply :: forall a b. f (a -> b) -> f a -> f b

Both get the same result though map transforms a function and apply transforms a function which is wrapped.

Maybe. They can be found in the modules Control.Apply, Control.Applicative and Data.Maybe. There are also instances for Either, Array, List, etc.

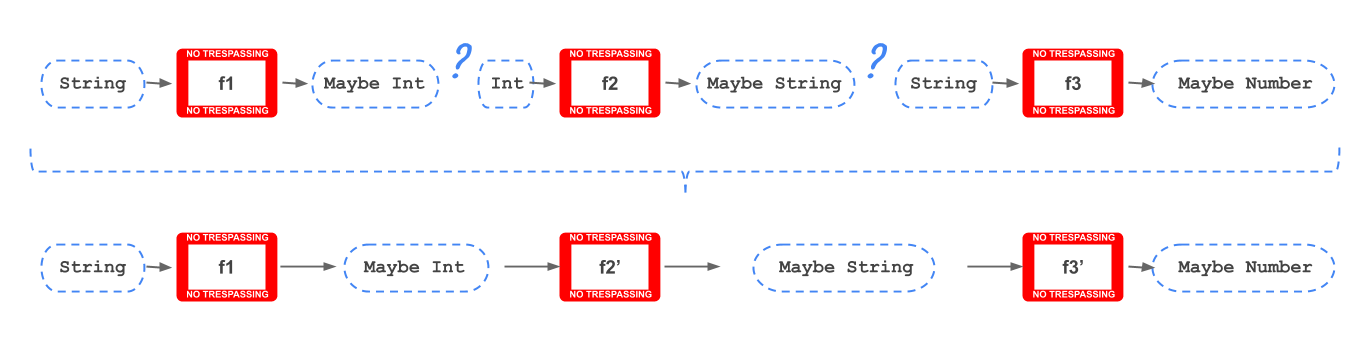

Monad

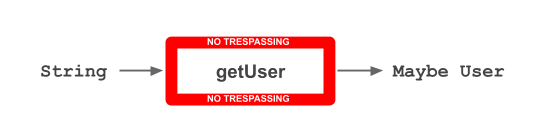

Let’s see what happens if we have a getUser function from a String value to a Maybe User value:

and we don’t have a String value available to be provided to the function but a Maybe String value.

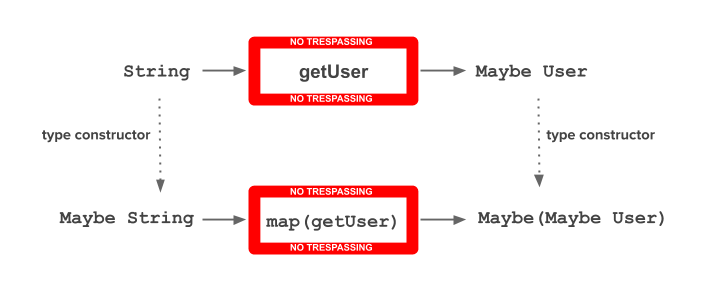

Then, we can think about the Maybe functor to have a Maybe String value as an input:

However, the result will be a Maybe (Maybe User) value.

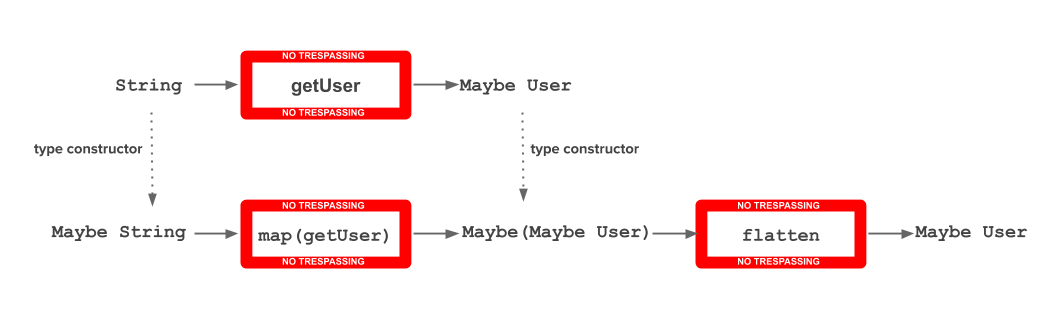

How can we get just a Maybe User value?

Flattening Maybe (Maybe User) into Maybe User:

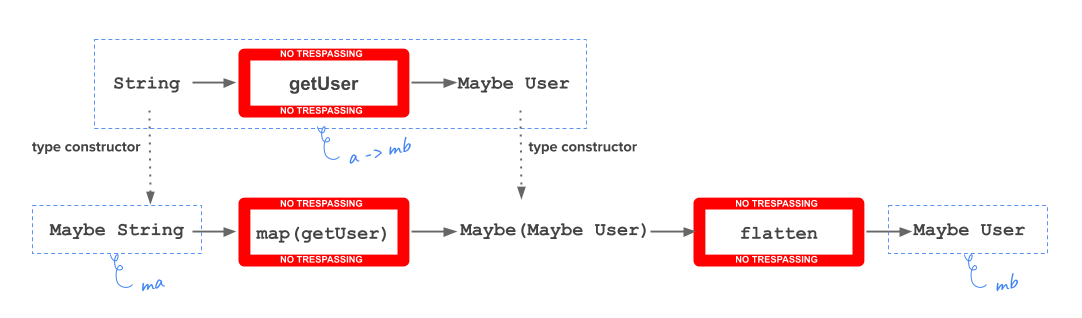

Both operations are considered together by bind from a monad:

bind :: forall a b. m a -> (a -> m b) -> m b

Following the example of the getUser function, it’s possible to get a Maybe User value from a Maybe String value, because the instance of Monad for Maybe is already available in PureScript:

user :: Maybe User

user = bind (Just "12345") getUser

or using an infix function application (in this case, >>= is the equivalent to bind):

user :: Maybe User

user = (Just "12345") >>= getUser

It’s said that monads are useful to chain dependent functions in series:

pure function from a functor. For instance, from a String value to a Maybe String value.

Further knowledge

- Talk: Truth about Types by Bartosz Milewski

- Post: The Science Behind Functional Programming by Rafa Paradela

- Post: Functors, Applicatives, And Monads In Pictures by Aditya Bhargava

- Online book: Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs by Harold Abelson, Gerald Jay Sussman and Julie Sussman

- Playlist: MIT 6.001 Structure and Interpretation, 1986 by Hal Abelson and Gerald Jay Sussman

- Online book: Category Theory for Programmers by Bartosz Milewski

- Specification: Fantasy Land Algebra

- Typeclassopedia

- Book: Haskell Programming from first principles by Julie Moronuki and Christopher Allen

Credit

Image by Anthony Jarrin from Pixabay